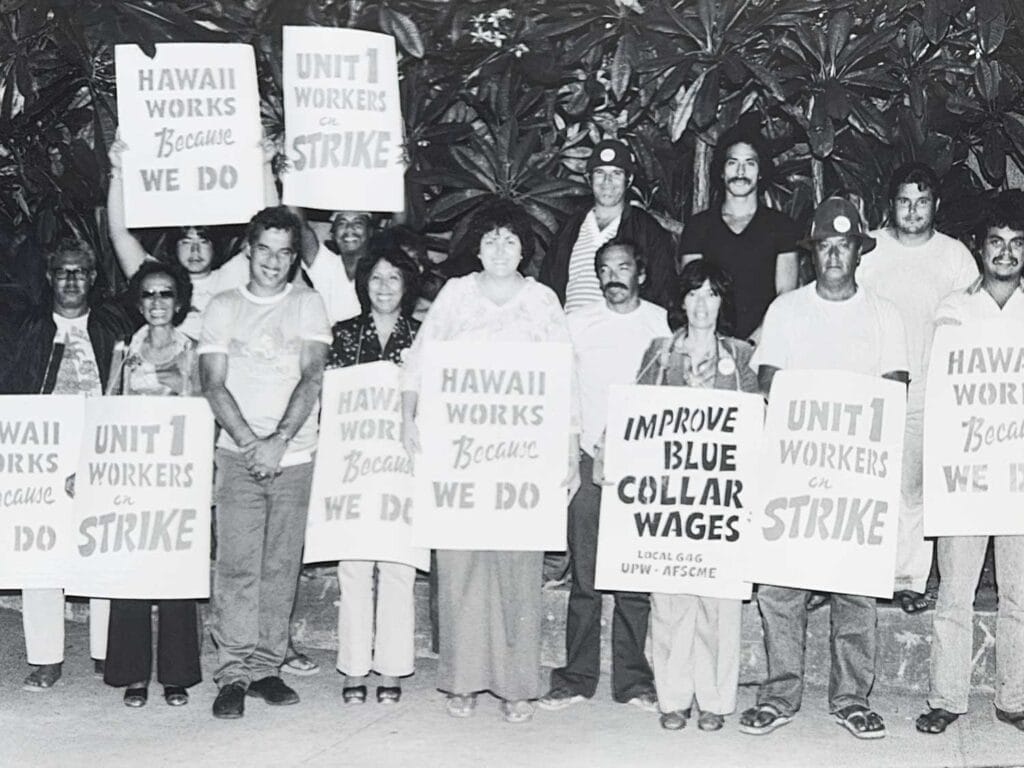

Just after midnight on October 22, 1979, UPW members working at the Honolulu International Airport set up the first picket lines and by 6:00am that morning, nearly all of the 7,700 Bargaining Unit 1 members were on strike. Trash collection halted and schools statewide were forced to close. Even the Hawaii National Guard was activated and put on standby by Lt. Gov. Jean King in fear that Correction Officers, who are members of Bargaining Unit 10, would honor the strike. State Director Henry Epstein said the National Guard showing up was one of the things that complicated talks and “it didn’t help negotiations at all.” However, he expected all prison guards to remain on the job due to an anticipated court order prohibiting non-striking public workers from honoring picket lines. HGEA had also announced its 16,000 members would honor the strike until that same court order forced their members back to work. However, they were instructed not to do any work handled by picketing Unit 1 members.

Unit 1 members, whose contract had expired at the end of June, included refuse collectors, custodians, maintenance workers, and school cafeteria staff and were among the lowest-paid government employees. The average salary of a Unit 1 member was $840/month, equivalent to just under $3,650/month today. But those at the bottom of the pay scale were making just $602/month or around $2,600/month in today’s dollars. A month earlier, Unit 1 members overwhelmingly voted in favor to strike with more than 92% saying “Yes.” And at 11:40pm on Sunday, October 21st, negotiations broke down and the go-ahead to strike was given.

By Friday of that first week, all but one of Hawaii’s 229 public schools were forced to close due to unsanitary conditions. The only school to remain open was the University of Hawaii Lab School. In addition, all adult community classes were canceled as well as the public’s use of DOE facilities. The closures prompted Gov. George Ariyoshi, who had been traveling in Asia since before the strike began, to cut his trip short and return to Honolulu to deal with the situation. The Governor’s trip was sponsored by the National Governor’s Association, and prior to leaving, Ariyoshi told reporters he was never asked by UPW to cancel his trip, which had been in the works since spring.

As the strike marched on into its second week, schools continued to remain closed as little progress was made on cleaning. One of the most noticeable examples of the strike could be seen at Honolulu International Airport. Trash cans overflowing with rubbish greeted visitors as they arrived, leading to the eventual closure of food concessions to limit the amount of litter and rotting food.

Entering its third week and with both sides still far apart on a deal, Superintendent Charles Clark promoted a plan to get students back in schools. The plan involved parents and volunteers helping to clean up schools so they could reopen. The Board of Education held an emergency board meeting on Friday, November 9th, and while the board voted 4-3 in favor of the plan, the proposal did not pass because five votes were needed to approve any action. One board member abstained from voting and the ninth member, Hiroshi Yamashita, was away on business with the National Education Association. Yamashita was able to return to the state in time for another emergency board meeting the following week and on Day 23 of the strike, the board returned a decision of 6-3 to move forward with the plan. The motion mentioned nothing about using volunteers to clean up, and several board members said the motion was deliberately kept broad to allow Superintendent Clark discretion on the use of volunteers and options on reopening schools. Clark admitted volunteers would be necessary for cleaning because out of 41 private cleaning companies contacted, only one was willing to cross picket lines but that company only had three employees. Two days later, on November 15th, more than 100 public schools reopened after being closed for 13 school days, and almost all had reopened by the end of the following week.

Then, a holiday miracle. A breakthrough was made the night before Thanksgiving when a tentative settlement was reached. The agreement called for a $100/month raise (equivalent to around $435 today) for the first 12 months of the new contract and an additional $100/month during the second year of the two-year contract. Some higher-paid tradesmen would receive an extra $15/month during the second year. There would also be overtime pay of up to 30 hours to clean up trash and debris accumulated during the strike. The next step was ratification. Epstein said UPW would continue its picket lines until the settlement was ratified.

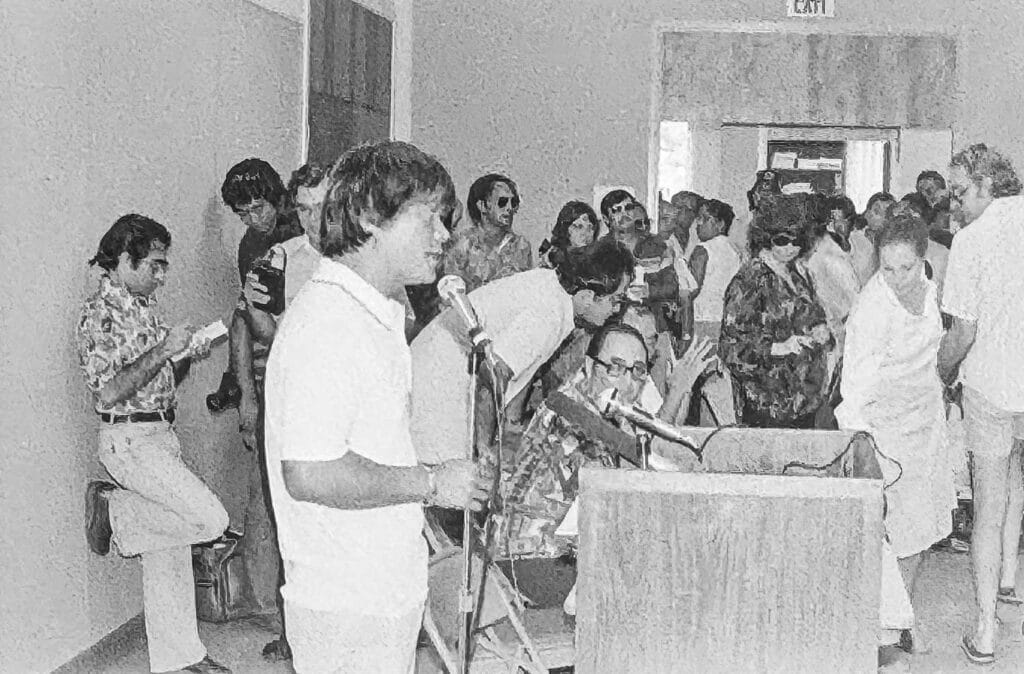

Ratification did not go smoothly. Following an emotional four-hour meeting, the Full Negotiating Committee voted 82-2 to recommend rejecting the tentative agreement. One of the two votes in favor of ratification being Epstein. However, some reasoned the overwhelming recommendation to reject was due to a roll call vote rather than a secret ballot. One unidentified union official was quoted saying, “The full committee would have easily endorsed the settlement package had the ballots been cast in private.”

Meanwhile, the Executive Negotiating Committee, the members who had been handling the negotiations, voted 7-6 in favor of accepting the tentative agreement. Neither of these were official decisions, however. The entire Unit 1 membership would vote on the settlement package a few days later due to a required 72-hour delay between mass meetings and balloting. In front of reporters, Epstein maintained confidence that members would accept the offer. But privately, he was heard saying he was worried.

On Saturday, December 1st, after 4 days of voting and unease by members across the state, the new contract was ultimately ratified by a 4-to-1 margin, and the 41-day strike came to an end. Along with the wage increases, the state also agreed to cancel suspension notices sent to some workers who refused to return to their jobs that were deemed “essential” to public health. During the walkout, the Hawaii Public Employment Relations Board had also attempted to levy $50,000 a day in fines against UPW. But with the strike now over, the issue was considered moot.

Most of the Unit 1 workers would return to their jobs on Monday and all would be back to work by the end of the week. Many agreed the outcome was a clear victory for Epstein, who endured internal criticism throughout negotiations. Robert Taira, the state’s chief negotiator, said “Despite the political infighting within UPW, it seems Henry Epstein’s leadership was vindicated by the members.” Epstein called the vote “a victory for the membership.”